Legacy

The Working Catholic: Race Relations by Bill Droel

Efforts these days to improve race relations are of related types. There is virtue signaling, as in ubiquitous TV ads featuring a mixed-race couple or the obligatory progressive statements from businesses and national religious denominations. There is social therapy, as when church-sponsored groups examine and then admit to their racism. Thirdly, justifiable racial grievances are expressed through marches and rallies that unfortunately lack any specific goal.

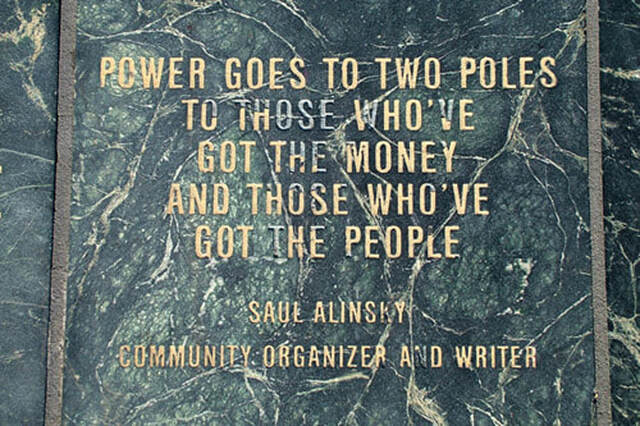

Saul Alinsky (1909-1972), considered the dean of community organizing, was known for his confrontational yet non-violent tactics, his sharp-edged comments and his exaggerated personality. Alinsky was a person of “keen sociological imagination” and “thoughtful action,” as Mark Santow details in Saul Alinsky and the Dilemmas of Race (University of Chicago Press, 2023). Alinsky never wavered from a commitment to equal dignity, regardless of race or ethnicity. Yet he was not ideological. He did not crusade for integration per se. He believed that if people have confidence in their own agency and in the democratic process, they will usually make better choices and support true pluralism. The problem, as Alinsky saw it, was the lack of power at the local level. There were too few viable mediating institutions through which people could effectively engage others. Thus, Alinsky dedicated his career to forming peoples’ organizations.

In 1938 Alinsky (then 29-years old) left his job at a university institute to, with Joseph Meegan (1912-1994), organize Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council (www.bync.org) in Chicago’s stockyards area. This is the first of Santow’s case studies. BNYC had a promising beginning. However, BYNC feared a possible influx of Black residents. The declining stockyards weakened the neighborhood economy. The older housing stock might appeal to Blacks. Thus, BYNC launched a conservation program. On the surface its beautification theme and its opposition to panic peddling and its campaign to upgrade infrastructure was constructive. The unspoken premise, however, was retaining white families in the area and prohibiting integration. Those white families and their institutions (principally churches) felt their defensiveness “was sanctioned by public opinion, economic sense and the law.” Many of those whites, Santow explains, did not realize how government housing programs were designed to “resist integration [through] subsidized suburban home ownership for whites while consigning Blacks to segregated urban neighborhoods.” (See The Color of Law by Richard Rothstein, W.W. Norton, 2017.)

A disappointed Alinsky avoided public criticism of BYNC. He only slowly admitted that, in Santow’s words, his effort “contributed to both the ability and willingness of [BYNC] to engage in racial containment…to protect and preserve an island of segregation.” Today BYNC says it “substituted an emphasis on community and economic development for Alinsky’s confrontational methods.”

In 1940 Alinsky formed his Industrial Areas Foundation. About 20 years later IAF returned to Chicago’s neighborhoods, starting with Organization for Southwest Community (Santow’s second case study).

Though OSC is overlooked in most chronicles of Alinsky, including the website of his foundation, the section on OSC in Saul Alinsky and the Dilemmas of Race is the most interesting. The area in 1959 was white with some upwardly mobile Black residents around its perimeter. IAF never said that integration was a goal of OSC. In fact, its organizers patiently and persistently solicited those mistrustful of Blacks. But many of those active in OSC were at best ambivalent, suspecting the goal was to move Blacks into the neighborhood.

OSC unraveled. Member groups exited. First, over an internal proposal to abolish term limits for officers. It was opposed by a faction who thought the hidden reason for the proposal was the retention of racially tolerant clergy officers. More groups quit OSC when its leadership drafted a letter to support an Illinois State bill on open occupancy. The measure could help neighborhood stabilization by giving Blacks more housing choices, particularly in the suburbs. But again, some OSC groups wanted nothing to do with racial improvements.

To judge by the Chicago neighborhood examples, Alinsky’s success was quite limited. Yet his moral stature, now 50 plus years since his death, remains high. Alinsky was consistently willing to risk failure in order to act in the real world. For Alinsky, too many people are “dismissive of messy compromises and far too enamored of the power and sufficiency of legislation and goodwill,” Santow concludes. Moralizing from the sidelines about race (or other issues) is cowardly.

Alinsky was constantly evaluating: Maybe a single neighborhood lacks enough power to deal with larger divisive forces. In 1970 his IAF organized a metropolitan organization, Campaign Against Pollution, soon called Citizens’ Action Program. Today the IAF has 63 county-wide or metro-wide organizations in the United States. Each is multi-issue and, like Alinsky, each believes that racial and ethnic relations improve as its member groups strive for the widest public conversation possible.

Droel edits INITIATIVES (PO Box 291102, Chicago, IL 60629), a newsletter on faith and work.

Efforts these days to improve race relations are of related types. There is virtue signaling, as in ubiquitous TV ads featuring a mixed-race couple or the obligatory progressive statements from businesses and national religious denominations. There is social therapy, as when church-sponsored groups examine and then admit to their racism. Thirdly, justifiable racial grievances are expressed through marches and rallies that unfortunately lack any specific goal.

Saul Alinsky (1909-1972), considered the dean of community organizing, was known for his confrontational yet non-violent tactics, his sharp-edged comments and his exaggerated personality. Alinsky was a person of “keen sociological imagination” and “thoughtful action,” as Mark Santow details in Saul Alinsky and the Dilemmas of Race (University of Chicago Press, 2023). Alinsky never wavered from a commitment to equal dignity, regardless of race or ethnicity. Yet he was not ideological. He did not crusade for integration per se. He believed that if people have confidence in their own agency and in the democratic process, they will usually make better choices and support true pluralism. The problem, as Alinsky saw it, was the lack of power at the local level. There were too few viable mediating institutions through which people could effectively engage others. Thus, Alinsky dedicated his career to forming peoples’ organizations.

In 1938 Alinsky (then 29-years old) left his job at a university institute to, with Joseph Meegan (1912-1994), organize Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council (www.bync.org) in Chicago’s stockyards area. This is the first of Santow’s case studies. BNYC had a promising beginning. However, BYNC feared a possible influx of Black residents. The declining stockyards weakened the neighborhood economy. The older housing stock might appeal to Blacks. Thus, BYNC launched a conservation program. On the surface its beautification theme and its opposition to panic peddling and its campaign to upgrade infrastructure was constructive. The unspoken premise, however, was retaining white families in the area and prohibiting integration. Those white families and their institutions (principally churches) felt their defensiveness “was sanctioned by public opinion, economic sense and the law.” Many of those whites, Santow explains, did not realize how government housing programs were designed to “resist integration [through] subsidized suburban home ownership for whites while consigning Blacks to segregated urban neighborhoods.” (See The Color of Law by Richard Rothstein, W.W. Norton, 2017.)

A disappointed Alinsky avoided public criticism of BYNC. He only slowly admitted that, in Santow’s words, his effort “contributed to both the ability and willingness of [BYNC] to engage in racial containment…to protect and preserve an island of segregation.” Today BYNC says it “substituted an emphasis on community and economic development for Alinsky’s confrontational methods.”

In 1940 Alinsky formed his Industrial Areas Foundation. About 20 years later IAF returned to Chicago’s neighborhoods, starting with Organization for Southwest Community (Santow’s second case study).

Though OSC is overlooked in most chronicles of Alinsky, including the website of his foundation, the section on OSC in Saul Alinsky and the Dilemmas of Race is the most interesting. The area in 1959 was white with some upwardly mobile Black residents around its perimeter. IAF never said that integration was a goal of OSC. In fact, its organizers patiently and persistently solicited those mistrustful of Blacks. But many of those active in OSC were at best ambivalent, suspecting the goal was to move Blacks into the neighborhood.

OSC unraveled. Member groups exited. First, over an internal proposal to abolish term limits for officers. It was opposed by a faction who thought the hidden reason for the proposal was the retention of racially tolerant clergy officers. More groups quit OSC when its leadership drafted a letter to support an Illinois State bill on open occupancy. The measure could help neighborhood stabilization by giving Blacks more housing choices, particularly in the suburbs. But again, some OSC groups wanted nothing to do with racial improvements.

To judge by the Chicago neighborhood examples, Alinsky’s success was quite limited. Yet his moral stature, now 50 plus years since his death, remains high. Alinsky was consistently willing to risk failure in order to act in the real world. For Alinsky, too many people are “dismissive of messy compromises and far too enamored of the power and sufficiency of legislation and goodwill,” Santow concludes. Moralizing from the sidelines about race (or other issues) is cowardly.

Alinsky was constantly evaluating: Maybe a single neighborhood lacks enough power to deal with larger divisive forces. In 1970 his IAF organized a metropolitan organization, Campaign Against Pollution, soon called Citizens’ Action Program. Today the IAF has 63 county-wide or metro-wide organizations in the United States. Each is multi-issue and, like Alinsky, each believes that racial and ethnic relations improve as its member groups strive for the widest public conversation possible.

Droel edits INITIATIVES (PO Box 291102, Chicago, IL 60629), a newsletter on faith and work.

Alinsky was a true believer in the possibilities of American democracy as a means to social justice. He saw it as a great political game among competing interests, a game in which there are few fixed boundaries and where the rules could be changed to help make losers into winners and vice versa. He loved to play the game.

- Sanford Horwitt, Alinsky's biographer

Alinsky's durability as both target for attack and organizational genius makes him a man of the current moment and many more to come. A nobody when he started out, Alinsky moves episodically through the country's polarized discourse more than five decades after his death.

He played with opposites, splits, divisions, paradox. He never joined up with any institution, religious or secular, and declared himself proud of it. Alinsky played devil’s advocate to himself by questioning the efficacy of the one institution in which he was most invested— the Industrial Areas Foundation. Like his namesake, David, he calculated how to maximize the impact of limited weaponry to beat intimidating powerhouses.

His anchor was democratic concepts and practices that didn’t align easily with capitalists or communists. If it can be said he had an ideology, that ideology would be centered on the actions of citizens embracing democratic practices, buttressed by a belief that most people, most of the time, will make good decisions about themselves and the world they inhabit. His self-declared partiality was toward the “have-nots” and their aspirations to gain a voice in decisions that mattered to them.

Alinsky sallied forth into the World-as-it-is without a road map for how to get to a better place: the World-as-it-should-be. For him that meant living in tension between the two - in that betwixt and between where people with conflicting views and different backgrounds confront, negotiate and compromise. Anyone following in his footsteps would have to do the same. Alinsky’s rebellious spirit and practical wisdom seeped into social justice organizing everywhere.

The David of Hebrew Scripture ascended to the throne of dominance, becoming a Goliath of sorts himself. Alinsky never took that path. Aware of his namesake’s ironic turn, he promised to organize against his own creations when/if they betrayed the democratic values he cherished.

Alinsky sallied forth into the World-as-it-is without a road map for how to get to a better place: the World-as-it-should-be. For him that meant living in tension between the two - in that betwixt and between where people with conflicting views and different backgrounds confront, negotiate and compromise. Anyone following in his footsteps would have to do the same. Alinsky’s rebellious spirit and practical wisdom seeped into social justice organizing everywhere.

The David of Hebrew Scripture ascended to the throne of dominance, becoming a Goliath of sorts himself. Alinsky never took that path. Aware of his namesake’s ironic turn, he promised to organize against his own creations when/if they betrayed the democratic values he cherished.

* Taken from Sometimes David Wins, by Frank C. Pierson, Jr.

The Man Beneath the Image

Alinsky was married three times. He met his first wife, Helene Simon, while attending the University of Chicago, and had two children, Kathryn Wilson and Lee David Alinsky. In 1947, Helene drowned while trying to save two children. Alinsky mourned her passing for many years.

His second marriage to Jean Graham was also to take a tragic turn. A diagnosis of multiple sclerosis proved to be the onset of serious mental health problems, which led to her hospitalization. Alinsky eventually ended the marriage, but maintained regular contact. In the year before his death, he married Irene McInnis.

Alinsky was married three times. He met his first wife, Helene Simon, while attending the University of Chicago, and had two children, Kathryn Wilson and Lee David Alinsky. In 1947, Helene drowned while trying to save two children. Alinsky mourned her passing for many years.

His second marriage to Jean Graham was also to take a tragic turn. A diagnosis of multiple sclerosis proved to be the onset of serious mental health problems, which led to her hospitalization. Alinsky eventually ended the marriage, but maintained regular contact. In the year before his death, he married Irene McInnis.

"Wherever democracy is revered and citizens seek power over decisions impacting their lives, his spirit and organizational genius is present. We need Alinsky now more than ever."

-Anonymous

ALINSKY'S BOOKS:

Reveille for Radicals;

John L. Lewis, An Unauthorized Biography;

Rules for Radicals.

Reveille for Radicals;

John L. Lewis, An Unauthorized Biography;

Rules for Radicals.